Exploring a New Detection Evasion Technique on Linux

Feb 25, 2021

#security #reversing #malware #linuxHere’s a new approach I’ve been trying out for evading advanced detection capabilities on Linux environments!

It’s now common knowledge that many Linux-based malware implants employ techniques to detect debuggers tracing their execution, from the classical PTRACE_TRACEME technique to trying to catch a SIGTRAP before the debugger does:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/ptrace.h>

/* Called to check if we are a child to a parent tracer */

if (ptrace(PTRACE_TRACEME, 0, 1, NULL)) {

printf("Is that a debugger I see??\n");

DoSomethingElse();

}

...

/* `someHandler` callback sets side effect `isDebugged`, which we can check after. */

signal(SIGTRAP, someHandler);

raise(SIGTRAP);

if (isDebugged) {

printf("Is that a debugger I see??\n");

DoSomethingElse();

}

/* No one's looking at us, do bad stuff! */

printf("We're fine!\n");

DoMaliciousStuff();

It’s not news that these techniques can all be beaten manually by an analyst in a number of ways. For instance, the simple ptrace antidebug can be broken by setting a breakpoint at the test rax, rax instruction after the ptrace syscall is made, and modifying the return value to continue without going to the branch where we’re caught:

gef➤ r

Starting program: /home/alan/Code/ebpf_evasion/a.out

Is that a debugger I see??

[Inferior 1 (process 3068) exited with code 0377]

gef➤ disass main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x00000000004017f5 <+0>: push rbp

0x00000000004017f6 <+1>: mov rbp,rsp

0x00000000004017f9 <+4>: sub rsp,0x10

0x00000000004017fd <+8>: mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x4],edi

0x0000000000401800 <+11>: mov QWORD PTR [rbp-0x10],rsi

0x0000000000401804 <+15>: mov ecx,0x0

0x0000000000401809 <+20>: mov edx,0x1

0x000000000040180e <+25>: mov esi,0x0

0x0000000000401813 <+30>: mov edi,0x0

0x0000000000401818 <+35>: mov eax,0x0

0x000000000040181d <+40>: call 0x43fd60 <ptrace>

0x0000000000401822 <+45>: test rax,rax

0x0000000000401825 <+48>: je 0x40183a <main+69>

0x0000000000401827 <+50>: lea rdi,[rip+0x817d6] # 0x483004

0x000000000040182e <+57>: call 0x40a8d0 <puts>

0x0000000000401833 <+62>: mov eax,0xffffffff

0x0000000000401838 <+67>: jmp 0x40184b <main+86>

0x000000000040183a <+69>: lea rdi,[rip+0x817de] # 0x48301f

0x0000000000401841 <+76>: call 0x40a8d0 <puts>

0x0000000000401846 <+81>: mov eax,0x0

0x000000000040184b <+86>: leave

0x000000000040184c <+87>: ret

End of assembler dump.

gef➤ b *0x0000000000401822

Breakpoint 1 at 0x401822

gef➤ r

Starting program: /home/alan/Code/ebpf_evasion/a.out

Breakpoint 1, 0x0000000000401822 in main ()

[ Legend: Modified register | Code | Heap | Stack | String ]

───────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── registers ────

$rax : 0xffffffffffffffff

...

────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

gef➤ set $rax = 0

gef➤ c

Continuing.

We're fine!

[Inferior 1 (process 3072) exited normally]

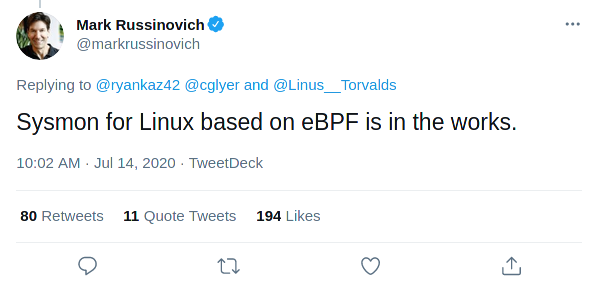

But, rather than playing the cat-and-mouse game and employing these manual mitigations against such techniques, many security engineers are now building up completely new detection tools, specifically in the container security realm, involving the eBPF subsystem to dynamically trace threats rather than use traditional debugging facilities. Let’s explore this a bit more in detail and build up something of our own!

eBPF and Threat Detection

eBPF, or the Extended Berkeley Packet Filter, is a really cool mechanism introduced in the Linux kernel since 3.15 for both security and systems profiling. I won’t go into in-depth details on its use, (check out awesome work here and here), but it essentially exposes a new compilation target where C code written for it is converted to a specific bytecode format, and fed to the kernel subsystem to enforce some type of monitoring functionality across the entire OS, whether it’s for tracing, network filtering, etc.

For detection engineers, this makes it easy to automatically bypass classical anti-analysis techniques that all assume some type of parent debugger spawning and latching onto the malicious sample. Rather than spending time manually reverse-engineering, it’s now possible to spawn threats and continue examining their capabilities without manual analyst intervention. So for security telemetry, rather than answering the question “how do I beat x anti-analysis technique”, eBPF instead answers “how can I beat all the techniques automatically?”.

However, as cool and revolutionary this technology is, I want to present a new anti-analysis technique where a malware sample propagated in any Linux environment can detect an active eBPF security monitor. But before we do that, let’s dive a bit into writing eBPF programs, and build our own telemetry agent first!

I Spy Malicious Behavior

As mentioned previously, eBPF programs all require a C program to be loaded and compiled to run in kernelspace. IOVisor’s bcc project helps provide a nice level of abstraction to do this, so we’ll use their bindings to Python to implement our “loader”.

eBPF allows a developer to instrument program functionality through several tracing interfaces. These come in many forms, such as uprobes (userspace function hooking), kprobes/kretprobes (kernel function hooking), and tracepoints. We’ll be using tracepoints because they are much more versatile, and have been well-documented and seen strong support.

Tracepoints are nice as they allow us to instrument and attach callbacks on a diverse set of system events, not just kernel and userspace functions. In fact, for our case, we’ll attach to the raw_syscall:sys_enter tracepoint to handle every system call executed for a specific target (this is also neat way to implement a strace clone).

So let’s create a file called bpf.c and implement the following template code. Follow along in the comments!

/* bpf.c */

/* Our Python loader will replace this for us when executed */

#define PID __PID

/* Represents a single event type we want to deal with */

typedef enum {

Output,

Exec,

Ptrace,

} type_t;

/* Represents a single event entry we want to pass back to the loader */

typedef struct {

int pid;

// in Python ctypes, this will be converted to an integer

type_t type;

// stores important strings parsed out of the system call event

char str[256];

} event_t;

/* Defines a lookup array with a single event we can retrieve from when parsing */

BPF_ARRAY(input_events, event_t, 1);

/* Creates a new ring buffer that we can read from in userspace */

BPF_PERF_OUTPUT(events);

/* We COULD ALSO attach to specific system call tracepoints

* (ie syscalls:sys_enter_ptrace), but we'll instead attach to ALL raw syscalls

* entering, and handle parsing register values individually.

*/

TRACEPOINT_PROBE(raw_syscalls, sys_enter)

{

// trace only the PID specified

u32 pid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() >> 32;

if (pid != PID)

return 0;

// instantiate new event for returning from lookup table

int zero = 0;

event_t *event = input_events.lookup(&zero);

if (!event)

return 0;

// set PID associated with event

event->pid = pid;

switch (args->id) {

// write case: get message printed if STDOUT

case 1:

event->type = Output;

bpf_probe_read_str(event->str, 256, (char *)args->args[1]);

break;

// execve case: get program name

case 59:

event->type = Exec;

bpf_probe_read_str(event->str, 256, (char *)args->args[0]);

break;

// ptrace case: we'll asssume PTRACE_TRACEME

case 101:

event->type = Ptrace;

break;

default:

return 0;

}

events.perf_submit(args, event, sizeof(event_t));

return 0;

}

Time for our telemetry agent! We’ll need to use the python-bcc package for this. Our goal is to spawn a new child process that represents our target

sample, but rather than using ptrace to attach and debug, we’ll instead load our BPF program, continue the child, and poll for events, which will be

handled by our callback!

Follow along in the comments!

#!/usr/bin/env python3

""" telemetry.py """

import os

import sys

import time

import ctypes

import signal

import bcc

# stores the eBPF C program we'll be running in the kernel

EBPF_PROG = "bpf.c"

# We need to first re-implement the event struct that was instantiated in the BPF program.

# As noted previously, the `type_t` enum ends up being an `int` in our loader.

class Event(ctypes.Structure):

_fields_ = [

("pid", ctypes.c_int),

("type", ctypes.c_int),

("msg", ctypes.c_char * 256),

]

class Agent:

def __init__(self, prog=[]):

""" Constructs a new security tracer agent """

# read initial source template

with open(EBPF_PROG, "r") as fd:

code = fd.read()

# if args to a binary is specified, spawn paused child and retrieve PID

self.pid = Agent._start_paused_child(prog)

code = code.replace("__PID", str(self.pid))

# pass finalized template for compilation with bcc

self.bpf = bcc.BPF(text=code)

@staticmethod

def _start_paused_child(arguments):

signal.signal(signal.SIGUSR1, lambda x, y: None)

signal.signal(signal.SIGCHLD, lambda x, y: os.wait())

# parse out executable and any supplied arguments

binary = arguments[0]

# fork a child process and start paused executable

pid = os.fork()

if pid == 0:

signal.pause()

os.execvp(binary, arguments)

return pid

def run(self):

""" Given an initialized agent, start tracing """

# first, register callbacks to use events are parsed

self.bpf["events"].open_perf_buffer(Agent.callback, page_cnt=2**8)

# resume execution

os.kill(self.pid, signal.SIGUSR1)

# loop and poll perf buffer

while True:

self.bpf.perf_buffer_poll(50)

try:

os.kill(self.pid, 0)

except Exception:

self.bpf.perf_buffer_poll(50)

break

time.sleep(3)

return 0

@staticmethod

def callback(cpu, data, size):

""" Parses event struct and outputs to user """

event = ctypes.cast(data, ctypes.POINTER(Event)).contents

# parse type enum as a string

typestr = ""

print("PID={} EVENT=".format(event.pid), end="")

if int(event.type) == 0:

print("write DATA={}".format(event.msg))

elif int(event.type) == 1:

print("execve DATA={}".format(event.msg))

elif int(event.type) == 2:

print("ptrace")

def main():

args = sys.argv

if len(args) < 2:

print("./telemetry.py [BINARY] <OPTIONAL_ARGS>")

return 1

prog = args[1:]

agent = Agent(prog=prog)

return agent.run()

if __name__ == "__main__":

exit(main())

Once both programs are done and in the same working directory, we can now launch it as follows:

$ sudo python telemtry.py ./malware

PID=4633 EVENT=execve DATA=b'./a.out'

We're fine!

PID=4633 EVENT=ptrace

PID=4633 EVENT=write DATA=b"We're fine!\n"

Nice! The previous sample that we’ve created executed the PTRACE_TRACEME technique, but our telemetry agent was NOT caught!

Defeating the Undefeatable

With eBPF, anti-analysis certainly becomes a much harder endeavor, since programs are all loaded in privileged processes and tracing through the kernel, rather than attaching to specific processes. This means that an attacker cannot simply profile the monitor’s memory mappings for allocated perf buffers in procfs, or fingerprint changes in sysfs pertaining to the BPF subsystem.

However, as I was doing research on this, one thing that intrigued me was this thread in the Linux kernel mailing list for BPF, which was a patch for logging BPF events to systemd! The author writes:

- Allow for audit messages to be emitted upon BPF program load and unload for having a timeline of events. The load itself is in syscall context, so additional info about the process initiating the BPF prog creation can be logged and later directly correlated to the unload event.

This means if we take a look at journalctl, say with the following command after we boot:

$ journalctl --system -n 100 --no-pager | grep BPF

Feb 22 16:58:19 alan audit: BPF prog-id=17 op=LOAD

Feb 22 16:58:19 alan audit: BPF prog-id=17 op=UNLOAD

We can see that auditd itself picked up a BPF program loading and tossed it back to us without needing elevated privileges!

This is great, as we now have a good lead for how we can implement an anti-detection/anti-debug for a sample that gets dropped in a monitored environment! Now do note that the specific eBPF program dumped in the logs is NOT our monitor, but rather systemd loading its own BPF program for a host-based firewall:

$ sudo bpflist

PID COMM TYPE COUNT

1 systemd prog 6

With this behavior observed, let’s implement a anti-detection heuristic programmatically using the sd-journal API exposed by systemd! We’ll implement the technique in the following manner:

- Parse the most recent journal log entries, as a security monitor will be launching a eBPF program just around the same time our malicious sample runs.

- Check for a BPF program load in those few entries, AND that it doesn’t have an unload, meaning that it’s still currently under execution.

- If such an event exists, we can assume that there’s someone snooping on us!

Let’s start off by importing the necessary header we need, and creating all the objects we want to interact with:

#include <systemd/sd-journal.h>

int ebpf_evasion(void)

{

/* open new journal object */

sd_journal *j;

if (sd_journal_open(&j, SD_JOURNAL_LOCAL_ONLY) < 0)

return -1;

/* get file descriptor and prepare for consumption */

if (sd_journal_get_fd(j) < 0)

return -1;

Once we get the file descriptor to where we can read from the system journal, we’ll start readng from the tail, and applying filters to match ONLY on MESSAGE events originating from the auditd subsystem, as that’s what is outputting the BPF load events:

/* seek to tail of event logs */

if (sd_journal_seek_tail(j) < 0)

return -1;

/* add filter on only audit events */

sd_journal_add_match(j, "_TRANSPORT=audit", 0);

sd_journal_add_conjunction(j);

At this point, we can start traversing and checking the recent entries! We’ll use a count of 5 to only examine the pass 5 events from auditd, but you can tweak this anyway you like:

/* we'll only traverse back to these number of entries. If there is a BPF program load in this

* set, we can assume that a security tracer became active as we ran our malware */

int count = 5;

/* flags gets set if a BPF program load is detected in the previous `count` entries */

int bpf_load = 0;

int bpf_unload = 0;

/* TODO: for more granularity, we can also check and store the BPF program ID */

/* use convenient macro to iterate through most recent entries */

SD_JOURNAL_FOREACH_BACKWARDS(j) {

if (count == 0)

break;

const char *data;

size_t len;

/* get message and parse if BPF call is involved */

sd_journal_get_data(j, "MESSAGE", (const void **)&data, &len);

if (strstr(data, "MESSAGE=BPF") != NULL) {

/* check if the program was loaded or unloaded */

if (strstr(data, "op=LOAD") != NULL)

bpf_load = 1;

else if (strstr(data, "op=UNLOAD") != NULL)

bpf_unload = 1;

}

count--;

}

/* cleanup */

sd_journal_close(j);

/* if the previous entries contained a full load cycle, we can assume that the program was

* detached and not monitoring us. However, if there is a load and no unload, we can assume it's

* still watching us.

*/

if (bpf_load && !bpf_unload) {

printf("Hey! Someone's snooping!\n");

return -1;

}

printf("Whew! No one's looking! Let's do malicious stuff!\n");

return 0;

}

Following along the code, we use the provided SD_JOURNAL_FOREACH_BACKWARDS to traverse the entries from the tail, checking to see if it contains the substring MESSAGE=BPF. If so, we’ll parse it further to see whether it’s a BPF program load or unload, setting the appropriate flags we’ve instantiated earlier. At the end of iterating the recent entries, we can assume that the sample is under scrutiny if a program was loaded, BUT NOT unloaded.

Awesome! Let’s compile this and see this in action:

As you can see, our sample has successfully been able to evade the eBPF monitor!

That’s all cool for our simple monitor, but what about tools being used in production in actual environments? Here’s the anti-detection in action against the bpftrace tool (full screen the cast for both panes):

Limitations

There a few limitations to this technique that I haven’t fully addressed, but will leave here to note for red teamers and malware developers who want to implement and scale up this technique on their own:

1. Reliability

Given the limited visbility into daemons and processes launching eBPF programs, not all will specifically be doing host-based threat detection and process monitoring! An attacker should always properly construct a threat model for the attack surfaces they are targeting, and appropriately fine-tune this method to minimize evading when it may clearly be a false positive!

2. Detecting Continuous Monitors

Some monitoring tools (ie AquaSecurity’s tracee) won’t operate ideally like we would like it to, as their eBPF detection programs are instantiated immediately as a system/container boots, pushing the BPF load cycle far above the event trail. We’ll delineate this behavior as continuous monitoring, and we’ll keep writing anti-detection code for it out of scope for this blog post, as it does get more complicated, and is definitely something I would like to do in pure Golang instead of C/C++. However the technique would be built off of our previous code, and would go as follows:

- Rather than track a few events, look at all events for the current boot. This would involve adding another filter

_BOOT_ID=<BOOT_ID_STRING>to parse out events only for the current boot session. - Create an associative array that stores entries for each unique eBPF program ID as a key, and a boolean representing a full load cycle (load AND unload).

- At the end of parsing journal logs, check the associative arrays for any programs that have not completed a full load cycle, and are still undergoing execution.

3. Static Linking

libsystemd does NOT support static linking, as mentioned here, which may not be ideal for portable samples that want to propagate in minified environments. However, most of our operations involve just parsing the journal log, so implementing our own library and statically linking that should be trivial.

Mitigations

All evasion / anti-debugging techniques have mitigations, and this one is no different. If you are a sysadmin deploying hosts or containers with the potential for getting attacked, and want to deploy monitoring capabilities onto them, here are suggestions:

- For hosts: explicitly configure

auditdto not ingest and output BPF program events that a malicious sample can snoop on. - For containers: definitely safer against this type of attack, but be sure to consider not setting up systemd / journal directly onto the container such that event logs are generated.

Detection engineers and analysts operating honeypots should also keep closer watch on file I/O events pertaining to /var/log/journal/* if implants do choose to start adopting such techniques.

Conclusions

That’s all for now! These techniques, both for detecting eBPF tracers and monitors, will be available on my menagerie project for anti-analysis.

I’m certainly not an eBPF expert, but have been pretty hands-on with the technology lately, and will update this post with any other detections I encounter. Please reach out to me if you definitely know more about the subject and have anything else to add!